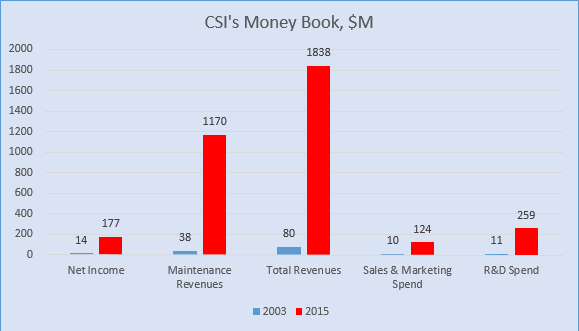

The book of the Toronto-based ERP apps vendor Constellation Software Inc.(CSI) tells a simple story – it makes good money as shown in its latest results of 2015 by ending the year with a 72% jump in earnings to $177 million on a 10% rise in total revenues to nearly $2 billion.

CSI used to be a little known on-premise software vendor with a knack of juicing up its returns by acquiring hundreds of small and niche vertical players since 2003, 31 alone in 2015. The strategy has worked so well that CSI now fetches a market cap of $8 billion. Even though CSI’s listing on the Toronto Stock Exchange has eased 14% to about C$515 from a high of almost C$600 since July 2015, the annualized return for its shareholders has exceeded 40% after it went public in 2006. By comparison, the annualized return on Cloud pioneeer Salesforce stock grew less than 26% during the same period.

In 2015, CSI became the largest independent software vendor in Canada, surpassing OpenText, which had held the No. 1 position for years following IBM’s 2008 purchase of the previous country leader Cognos. Like OpenText, the majority of CSI’s revenues comes from United States and Europe.

At a time when many applications vendors are embracing the Cloud but incurring steep losses along the way, the experiences of CSI raise some interesting questions about the future of the software industry.

Good Money On Software?

Can on-premise software companies continue to make money consistently in this new era of digital disruption? Are Cloud companies fundamentally a money-losing proposition because they spend so much on infrastructure and even more on sales and marketing?

Generally speaking, Cloud or on-premise software companies make good money, perhaps much more so than soda bottlers and drug makers because digital production and distribution costs are negligible. With Cloud delivery, the opportunities for making more money are enormous given the ease to reach a global user base with the help of cheap infrastructure courtesy of someone like Amazon Web Services.

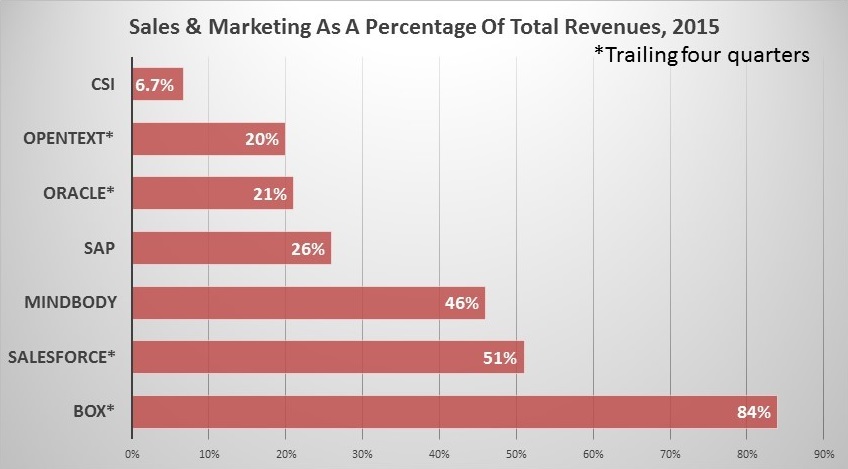

The reality is quite different. Cloud apps vendors like Box, Salesforce and Mindbody(which competes with the club-membership apps unit of CSI) routinely spend two to four times more on sales and marketing than what other software providers like Oracle and SAP do as a percentage of total revenues as shown in the following graphic. And it could be years before many of these Cloud apps vendors that spend lavishly to expect to turn a profit consistently.

CSI has been relentless driving its sales and marketing costs down since 2003 when its sales and marketing spend was 13% of its revenues. In 2014, it went down to 7.1% and last year it fell even further to 6.7%. Through the period, its revenues soared from $80 million in 2003 to $1.83 billion in 2015, a 23 times climb. Its sales and marketing spend rose from $10 million to $124 million, a 12-fold increase. Corresponding to its overall growth, its research and development spend as a percentage of total revenues increased nearly 26 times from $10.6 million in 2003 to $259 million last year.

One of the reasons behind its relatively meager sales and marketing spend has to do with the nature of its customer base. It sells into about 85,000 organizations across scores of verticals like local government agencies and subverticals like cabinet manufacturing. Many of its customers have been running these applications for decades and there is little need for CSI to boost sales and marketing spend just to get a few dollars extra from them on new modules or enhancements.

Instead, CSI invests in maintenance in hopes of extending the recurring revenue stream for a long time. Last year, for every dollar CSI put into maintenance, it yielded nearly $7. At Oracle, the enterprise software giant pocketed $16 for every dollar it spends on maintenance. Maintenance represents about 64% of CSI’s revenues, while maintenance and Cloud revenues make up about 61% of Oracle’s revenues.

Most acquisitions that CSI make are small spending no more than $5 million a pop on average. What it does well is the classic buy low and sell high strategy. In October 2015, CSI’s Quadramed unit acquired the hospital solutions operations from QSII picking up about 100 rural and community hospitals as customers. QSII said the sale was immaterial as the operations were losing money and its revenues tumbled to almost nothing in 2015 from $4.4 million a year earlier.

Similarly CSI bought CareTracker and Picis in late 2014 and May 2015 from UnitedHealthcare’s OptumInsight. Adversely impacted by the ACA legislation, United Healthcare and its OptumInsight unit have been focusing more on its analytics and coding business, while unloading noncore apps assets like CareTracker for practice management and Picis for emergency departments.

Following the Brexit vote on June 23, 2016, CSI proceeded with a cash offer for UK-based Bond International, which sells a range of HR, payroll and talent management apps for £44 million. Before it made its move, CSI had already accumulated Bond shares representing about 30% of the vendor. In July 2016, Bond rebuffed the overture from CSI by divesting its HR and Payroll unit to FMP Global Bidco Ltd, a UK-based HR and payroll firm backed by Tenzing Private Equity. FMP said it was paying £27.4 million and the assumption of £2 million of net debt for Bond’s HR and Payroll unit. After the sale, Bond is expected to mull over future of its remaining assets including recruiting apps, real estate, etc.

Whatever the outcome, these are what CSI president Mark Leonard refers to as distressed assets that his company can turn around and continue to profit by squeezing the remaining money-making opportunities in maintenance and support.

Leonard, who founded the company in 1995, takes pride in the decentralized structure of CSI. Its head office in Toronto keeps a skeleton staff – a little over a dozen – that manages such functions as M&A, finance, compliance and mentoring. According to Leonard, its head office expense as a percent of net revenues halved from 1.9% in 2005 to 0.9% in 2014, the latest data available in his annual letter to shareholders.

Last year, Leonard went even further by asking his board to cut his total compensation to zero, saving about $1 million for CSI. The former venture capitalist, who owns a 6.7% stake in the company worth about $535 million, said instead of charging his company for coach tickets on business trips, he would pay for such travels out of his own pocket. That way, he considers himself not as a CSI employee, but rather a shareholder whose sole interest is to ensure the CSI business is sustainable and viable for the long haul.

The rest is up to thousands of CSI employees located around the world running nearly 200 business units with the biggest employing about 500, trying to serve their customers better and ultimately making a buck out of their software IP. Instead of passing out options, CSI offers them incentives in the form of shares escrowed for three to five years.

CSI’s Future

Following the financial crisis, CSI saw declining sales in its construction software business and its acquisitions were briefly interrupted. In May 2011, CSI announced that it would explore strategic options, a prelude to putting itself up for sale. That did not happen.

Subsequently, CSI made more acquisitions including some of its biggest deals like TSS for its healthcare, property tax and civil affairs apps in the Netherlands for €240 million. The recent purchases have also opened up new revenue models including Software as a Service. In 2014, 17 business units at CSI generated more than half of their revenues by hosting applications on behalf of customers and their recurring revenues represented 13% of its maintenance stream.

Similar to other Cloud vendors, CSI faces the same challenge of higher than normal churn rates among its SaaS customers, while racking up bigger expenses in acquiring or retaining them. That renders the Cloud less financially attractive than its on-premise business, according to Leonard.

Another challenge facing CSI is its foray into the healthcare vertical, a notoriously difficult market for many ERP vendors. Sage, for instance, sold its healthcare apps business for a loss of $108 million to Vista Equity Partners in 2011 after years of failing to turn the former Emdeon division around.

It’s possible that CSI has seen some sluggishness among its TSS healthcare customers with its professional services revenues(a prerequisite and substantial part of most healthcare apps implementations) dropping 16% in 2015, having contributed heavily to its top line in 2014 after the completion of the TSS purchase in December 2013.

With IBM spending $4 billion in recent months to bulk up its healthcare software portfolio including the recent purchases of Merge for medical imaging and Truven Analytics for Big Data, CSI may need to reevaluate its options in the healthcare vertical. Without a defensible niche in healthcare, CSI could end up competing on the sidelines and not being able to add incremental gains to its mix.

Leonard gives little hint on what he wants to do next with CSI other than continuing its acquisition-centric strategy, while positioning himself as someone with a vested interest in the long-term health of the company. In his letter, he suggests that he may want to travel less, but if he does he will fly first class in greater comfort. Also, he would recommend books on such enlightening topics as prisoner game dilemma and loss aversion to better oneself.

In the same vein, while it may sound altruistic for giving up his compensation for the good of the tribe, Leonard is fully convinced that the best chapters of CSI’s money book have yet to be written.