Seismic shifts in the technology world have sparked a wave of unlikely partnerships involving desperate vendors pairing up with one another in order to protect their turf.

Listening to their announcements, one could sense an air of desperation from executives who normally find themselves confident and at ease after years of steering the high-tech industry to new heights, confounding naysayers and winning admiration from legions of loyal customers. At times, these tech tycoons were courting partners with such ardor that it sounded as if they were aging housewives trying to outdo one another with the latest plastic surgery techniques, all in the name of wanting to look attractive and desirable once again.

The cast of characters included a stylish CEO who indulges in the blood sport of high-tech sailing, a Austin, Texas, college drop-out who tries to save his company, a bald software magnate who cherishes his grip on the PC market as his legacy, and a San Francisco native who takes great pride in his city.

At the center of this high-risk facelift is Oracle CEO Larry Ellison, who aims to win this year’s America’s Cup sailing competition with his 72-foot-long catamarans that use computer-controlled fixed sails in order to kick off Oracle’s biggest annual customer conference with both events being held in San Francisco in September. A sailor of the competing team was killed in May after his boat capsized while training in the San Francisco Bay.

Dial Dell For Oracle

Four days after Oracle closed its fiscal 2013, it signed a deal with Dell to broaden the distribution of its software including Oracle Linux, Oracle VM, and Oracle Enterprise Manager, which will be optimized to run on x86 servers from Dell. In addition Dell will be providing direct support to customers buying such integrated solutions in a rare display of unity between the two companies, which have been competing head-on in the hardware market since Oracle bought Sun in 2010.

Ostensibly Oracle was going to bed with Dell because it wanted to sell more software to Dell customers perhaps at the expense of its own hardware products, which not surprisingly are optimized to run Oracle Linux, Oracle VM, and Oracle Enterprise Manager.

Another good reason for signing Dell is that Oracle has indicated its desire to give up on the x86 server market and instead focus on its high-end Engineered Systems, which saw its bookings reaching 3,200 units in fiscal 2013. That figure represented about one-third of its hardware system revenues. Still two-thirds of its hardware systems revenues, including Storage, would be worth $2 billion in projected fiscal 2014 revenue. Unless Oracle wants to completely replace its hardware business with Engineered Systems, it might still be selling low-end machines for the foreseeable future.

So why bother with Dell? The simple answer is that Dell could be used to compete with HP on the low end even though Dell’s own future is fraught with uncertainty as its founder Michael Dell has been trying to save his company through a controversial buyout deal to take the PC maker private. After falling out with HP, Oracle is determined to sell its software through a cadre of value-added distributors like Arrow and Avnet, which put them onto x86 servers from a variety of hardware vendors. The deal with Dell allows Oracle to assert control over who gets its software and how it can be tweaked to meet specific customer requirements. Dell apparently fits the bill.

If Dell is desperate enough to be the pawn for Oracle to compete with HP, why shouldn’t its salespeople fight tooth and nail with these VADs for the business of anyone needing new boxes for their data centers?

So Oracle may be able to let someone else do the dirty work of selling low-margin x86 servers, it does not mean that the end results would be that clean cut.

The second reason behind this flawed strategy is that why would anyone want to buy souped-up servers from Dell other than customers that already plan to run Oracle applications, or for that matter those standardizing on the Oracle Red Stack. The only difference is whether they would be running the apps or databases on Oracle boxes or Dell’s. In that respect, Oracle may not necessarily be able to expand its reach, but rather segmenting customers into two classes.

High Class vs. Low Class

Class A would be those that buy high-end engineered systems, Oracle software and Oracle support directly from Oracle. These are primarily the 2,000 key accounts that represent the bulk of its revenues in any given year. For those that buy engineered systems and software from its VADs under specialization programs, they are increasingly being asked to sign Oracle support contracts in order for the VADs to get the maximum channel incentives.

Class B would be everyone else that can go to vendors like Dell who sell x86 servers, Oracle software and Oracle-approved support, which is going to be sold through Dell. The message to the customers is that if they don’t buy engineered systems from Oracle, chances are they probably can’t afford to buy support from Oracle anyway. These customers are no less important than Class A. It’s just that they are perhaps more price-sensitive.

After a bruising battle to shore up its hardware business, which Oracle expects to grow again in fiscal 2014, the segmentation strategy makes it abundantly clear that Oracle can no longer afford to be all things to all people.

Which raises the most basic question of all? If Oracle did not want to be all things to all people, would it have done better by investing the $5.6-billion that it paid Sun in strictly software outfits like Citrix, Athenahealth, or even LinkedIn, all of which have done better than Oracle in terms of stock performance and public acceptance over the past three years.

Oracle’s Third Miss

In the meantime, Oracle took a beating on June 20 when it announced its fourth-quarter results, which typically generate its biggest revenues for the year. The disappointing fourth-quarter results, following two misses in the preceding three quarters, prompted a 9% drop in its stock. In every key product category, Oracle failed to keep up with the growth of its closest competitors when comparing its fourth-quarter revenues with those of its peers in their latest three-month period, as shown in the following table. During the earnings call, Oracle executives blamed the shortfall on the cooling trend in once-hot markets like Australia, Brazil, and China.

Comparing Hardware, On-Premise Software, Cloud Applications Revenues From Vendors’ Latest Quarter

| Segment | Revenue Type | Latest Q in 2013 , $M | Same Q in 2012, $M | Y:Y Change, % |

| Hardware Systems | EMC’s Product Revenues | 3112 | 3069 | 1% |

| Hardware Systems | HP’s Storage and High-End Servers | 1123 | 1139 | -1% |

| Hardware Systems | Oracle Hardware Product Revenues | 849 | 977 | -13% |

| Hardware Systems | IBM Hardware | 3106 | 3749 | -17% |

| Hardware Systems | Teradata | 249 | 308 | -19% |

| On Premise | Microsoft Dynamics | 400 | 353 | 13% |

| On Premise | Microsoft Servers & Tools | 4023 | 3627 | 11% |

| On Premise | Infor’s License, Subscription | 182.3 | 166.5 | 9% |

| On Premise | SAP’s On-Premise License | 854 | 828 | 3% |

| On Premise | IBM Software | 5572 | 5600 | -1% |

| On Premise | Oracle’s Software License | 3768 | 3814 | -1% |

| On Demand | SAP Cloud | 178 | 38 | 368% |

| On Demand | Workday’s Subscription Revenues | 68 | 37 | 85% |

| On Demand | Oracle’s Cloud Applications Revenues | 258 | 171 | 50% |

| On Demand | Salesforce.com’s Subscription and Support Revenues | 842 | 655 | 29% |

| On Demand | Ultimate Software’s Recurring Revenues | 78 | 61 | 28% |

| On Demand | Intuit’s QB Online, Enterprise, Desktop Subscriptions | 184 | 151 | 22% |

Souce: Apps Run The World

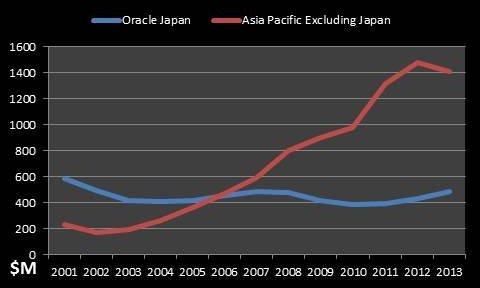

The revelation ran deeper than that. Based on our modeling, Oracle’s hot selling streak for its software licenses, especially those of its core database, ended in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2013 in much of Asia Pacific for the first time since the Dot Com bust in 2001. The situation was so bad that the estimated $98 million shortfall in license sales of database and middleware, resulting in a 21% drop in software product revenue, practically dragged the whole year into the deficit column for Asia Pacific except Japan.

Oracle’s Asia Pacific Excluding Japan Software License Revenues in 4QFY13, $M

Products | 4Q13 | 4Q12 | Change, % |

Database/Middleware | 371 | 469 | -20.9% |

Applications | 76 | 76 | -0.5% |

| Total | 447 | 546 | -18.1% |

Since 2001, the Asia Pacific economic miracle that has helped sustain growth for so many multinationals including Oracle seems to be turning its nose at them. During that period, Oracle saw its software license revenues balloon nearly $1.5 billion from $221 million. In its fiscal 2013, those revenues dropped 5% to $1.4 billion, as shown in the following graphic.

In Asia Pacific excluding Japan, its database and middleware license revenues tumbled 21% to $371 million, while its applications were flat for the last quarter of fiscal 2013. After years of growing its Asia Pacific operations, Oracle Japan now only represents less than 30% of its business in the region.

Things were not better in other parts of the world. While Oracle executives cited Brazil for hurting its software performance in the latest quarter, its global picture also looked bleak. In fiscal 2013, Oracle’s software license and subscription revenues, net of acquisitions, fell from $9.9 billion to $9.8 billion in the previous year.

A more troubling trend emerged from its fiscal 2013 results. As Oracle started expanding its presence in Cloud applications by acquiring vendors such as Taleo for eRecruiting, RightNow for Cloud CRM and Eloqua for eMarketing, its core database and middleware license revenues fell 2% for the year, as shown in the following table.

Oracle’s Software License Revenues, Fiscal 2011-2013, By Product, $M

| FY2011 | FY2012 | FY2013 | FY12-FY13 Growth, % | |

| Database & Middleware | 6626 | 6971 | 6839 | -1.9% |

| On-Premise Apps | 2347 | 2480 | 2572 | 3.7% |

| Cloud Apps | 262 | 455 | 910 | 100.0% |

| Total | 9235 | 9906 | 10321 | 4.2% |

While economic issues might have played a role behind the decline, increased popularity of open-source databases as well as Hadoop framework for data store in Big Data projects has undermined the growth of Oracle database, based on our continuous research on more than 2,000 customers.

Vendors such as 10gen with its open source database MongoDB as well as a slew of others have eaten into the markets previously dominated by Oracle. 10gen, for example, saw its revenues jump 20 times as it completed a series of funding that totaled $70 million in recent years. Many of the 10gen salespeople were hired from Oracle where they had years of experience selling millions of dollars of Oracle databases every year. Giant insurer Metlife recently embarked on a $300 million IT project with special emphasis on using open-source database for a central repository of customer interactions. Then there was SAP, which over the past two years has signed over 1,500 customers for its in-memory database product called SAP HANA. It was a milestone that largely came at the expense of Oracle since many of these customers would have continued to run Oracle database if not for SAP HANA.

While SAP HANA might well be the straw that broke the camel’s back, other options such as open-source databases from an assortment of startups and infrastructure as a service offerings from mega-vendors such as Amazon could make it difficult for Oracle to reverse the database downward spiral, despite its successes of bundling the software with its engineered systems like Exadata.

Having sold more than 6,000 Engineered Systems including primarily Exadata and Database Appliances since fiscal 2009, Oracle has managed to develop a new channel of captive database customers. Still the math works against Oracle because there are more than 250,000 database customers. For every Exadata and Database Appliance unit that goes out attaching a copy of Oracle database, there are at least 100 current Oracle database customers that could switch to competing offerings because of their reluctance to fall in line with the Oracle’s hardware and software working together message, an expensive bundle in the minds of those accustomed to commodity servers.

Like many successful companies, Oracle has the good fortune of amassing a huge number of database customers, which not surprisingly have also resulted in massive displacement opportunities for rivals that promise easier and cheaper implementations. Since the mainframe days, that has always been the rule of technology industry with each new wave cresting and taking down the incumbents by the sheer force of better price and availability. Both Oracle and its new partner Microsoft understand this all too well.

From Redwood To Redmond

On June 24, Oracle and Microsoft announced a partnership that will enable customers to run Oracle software on Windows Server Hyper-V and in Windows Azure. Customers will be able to deploy Oracle software — including Java, Oracle Database and Oracle WebLogic Server — on Hyper-V or in Azure and receive full support from Oracle.

On the surface, the alliance between the two would help plug a major hole in the latter’s enterprise strategy, namely bringing Oracle’s lucrative database customers to Azure, Microsoft’s Cloud computing platform, thereby generating a reliable recurring revenue stream.

Oracle’s support of Microsoft HyperV virtualization technology will loosen the hold of VMWare on Oracle customers, opening up new opportunities for Microsoft and Oracle to sell their Big Data, storage, and security products.

It’s not clear what effects the new alliance between Oracle and Microsoft will have on Oracle products like Oracle VM, which competes with HyperV and VMWare. Or for that matter, what would happen to Oracle’s nascent Platform As A Service offerings like Java Cloud and Infrastructure As A Service led by Oracle Database Cloud, both of which have been launched with much fanfare during the third quarter of its fiscal 2013? It’s equally tempting to ask how many more Azure customers would Microsoft be able to add with this new alliance. Microsoft has publicly stated that the customer count of Azure has reached 200,000, up from 10,000 in 2010.

No commitments were spelled out in the press release announcing the Oracle and Microsoft partnership. Neither side said they would be adopting each other’s technology. From the revenue standpoint, it was not clear how much would either side be able to gain from the alliance.

In the short history of personal computing, the partnership that appeared to have withstood the test of times remained that of Microsoft and Intel. Both sides have profited tremendously from their duopoly because each studiously avoided competing with the other, while collaborating to ensure a sustainable PC ecosystem.

That market has been withering in wake of the proliferation of mobile devices. There were times when an alliance with Microsoft shook the world. There were deals with IBM on jointly developing the OS/2 operating system in 1987, Sun on a technology collaboration arrangement in 2004, as well as scores of other major alliances with Adobe, Apple, Nokia, Novell, and more recently with Yahoo on search in 2010. In February 2013, Reuters reported that the new CEO of Yahoo Marissa Mayer said both companies wanted to “collectively want to grow share rather than just trading share with each other.’’

Microsoft’s Makeover

Steve Ballmer, the CEO of Microsoft, oversaw many of those alliances. After missing its chances to win in search, mobile and tablet markets, Ballmer appears to be hitching his PC legacy to enterprise computing and the Oracle partnership could well be his best hope to fend off Cloud competitors by concentrating their database fire power.

If Dell thinks its deal with Oracle will help it expand in the enterprise market, there’s every reason to believe that the Microsoft’s deal with Oracle could help both move the needle by convincing enterprise buyers that their interoperability will benefit them in the long run. Incidentally Microsoft has also been readying its next SQL Server database release later this year with in-memory capabilities. Similar to the on-again, off-again battle between Dell and Oracle, competition between Microsoft and Oracle in their core market may persist in the Cloud and elsewhere.

This is not to suggest that neither Microsoft nor Oracle would come out ahead in this unlikely partnership. Given the pressures both sides facing in Cloud computing, it’s surprising that they are equally noncommittal on how much and to what extent would they want to invest in such a partnership. It also underscores the fact that the rationale behind the alliance has more to do with banding together to lock out Amazon and VMWare in order to prevent their installed base from being penetrated by the enemies. An account that is being overrun by one vendor or perhaps two is better than that of three or more. It’s the classic tale of an enemy’s enemy is one’s best friend.

Still, one begs to question for a company the size of Microsoft or Oracle, what more could they gain from working with each other if they are not going to put some skin in the game.

One of the biggest reasons behind the latest wave of alliances has to do with the simple fact that the IT marketplace is maturing and that is particularly apparent in the enterprise as companies need to consolidate their data centers as part of their overall strategy to reduce costs, while maximizing every penny they spend.

Instead of operating 10 data centers, they may now want three, one for each region. Instead of having three data centers with one each in Americas, Asia Pacific, and Europe, they want everything in a private cloud preferably operated by a global provider for the entire Cloud infrastructure.

The Amazon Cloud

For the moment, the most attractive girl at the party is Amazon with its Amazon Web Services, which has enjoyed rapid adoptions of its public cloud infrastructure over the past few years. Instead of running data centers and all their applications on their own, customers go to AWS Marketplace, picking and choosing the software they want to run. Then they start a payment plan for as little as 99 cents an hour and off they go. No hardware to lug around the globe and no software to manage.

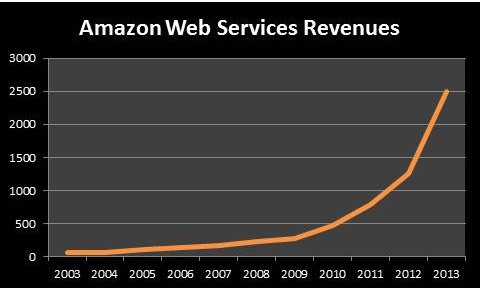

Currently AWS revenues are listed along advertising services and co-branded credit card agreements in the so-called non-retail activities. In our estimate, Amazon AWS, which started out as Merchants.com and later became Amazon Enterprise Services has grown to $1.3 billion in 2012, up from $55 million in 2003 as shown in the following graphic. This year AWS revenues could top $2.5 billion. Wall Street estimates for AWS revenues run as high as $3.8 billion for 2013.

While a potential technology sharing deal between AT&T and Verizon could raise the objections of the Justice Department because of their concentration of customers in the United States alone, the alliance that covers database technologies between Oracle, the No. 1 database vendor, and Microsoft, the No. 2, has barely registered any concern from regulators or their customers. The conclusion is that their agreement could not give anyone undue advantage in the database market because it has become a commodity where low-priced alternatives are abundant. Open-source databases like 10gen, along with Hadoop framework, which has become the preferred data store for many companies, have tilted the balance of power away from two of the largest database vendors in the world. The absence of objections from anyone suggested that such a deal could not matter much.

Microsoft and Oracle will continue to duke it out in the database market in spite of the alliance. What does matter is that both sides agreed to partner based on the same conclusion – not doing such a deal could leave them more exposed than ever. It was the lesser of two evils.

It was also ironic that following its purchases of RightNow and Taleo, Oracle’s fortune – at least from a market cap standpoint – kept slipping. And the two blockbuster partnerships with Dell and Microsoft, also failed to remake its image as most watchers were zeroing in on its fourth quarter results. It appeared that Oracle’s golden touch failed to work its magic anymore when its fundamentals ceased to impress.

To further embellish its Cloud image, Oracle also signed a deal in the same week with NetSuite and Deloitte, which will be selling joint solutions including Fusion HCM apps and Netsuite financials, all running in the Cloud. It’s hard to quantify the sales effects of the alliance between NetSuite and Oracle because of their historic ties. Oracle’s Ellison continues to be the majority shareholder of NetSuite. It probably would make more sense for NetSuite to expand in areas not being covered by Oracle in order to help both broaden their reach. By working with Oracle more closely than ever, NetSuite appears to be taking the opposite tack needed to expand its own franchise. Another paradox is that NetSuite has been pushing its own ecosystem called SuiteApp.com, which features 22 HCM products from its partners. The new alliance between Oracle and NetSuite could only mean more competition for NetSuite partners in the HCM space.

Let’s Go To Bed

In the meantime, Oracle’s attempts to remake its image continued. A day later, Oracle announced that it would go to bed with Salesforce.com in its last-ditch facelift. On the surface, it was a good deal for both. Oracle’s 24,000-strong sales force will use Salesforce.com products for sales force automation, potentially scaling back the use of its own Siebel products. On the other hand, Salesforce.com, which has close to 10,000 employees, will start running Fusion HCM and Financial Cloud from Oracle. Based on list prices, Oracle could end up paying Salesforce.com $37.5 million in annual subscription, while Salesforce.com could be paying Oracle $7.86 million for component license and support fees for Fusion Applications.

The actual prices could run much lower. In Oracle’s last fiscal quarter of 2013, discounts of up to 38% were given to customers for buying several million dollars worth of products, according to our field research. It’s equally important to point out that both sides may not start implementing these products for years to come. It took Oracle years after the purchase of Siebel to start running Siebel for sales force automation. There is no reason to believe that the implementation of Salesforce.com within Oracle will be any quicker. After making a series of acquisitions including the pending ExactTarget purchase for eMarketing, Salesforce.com is saddled with a host of HR and financials systems including Oracle E-Business Suite, Taleo, and Workday. It is possible that the ERP rationalization project within Salesforce.com will also take years.

The real gem in the alliance between Salesforce.com and Oracle lies in the use of Oracle database by Salesforce.com, which could become the perfect substitute for SAP. Earlier SAP has indicated its desire to end its use of Oracle databases on any new sale of its applications, which can now run on HANA for better price performance than that of other databases including Oracle, according to SAP.

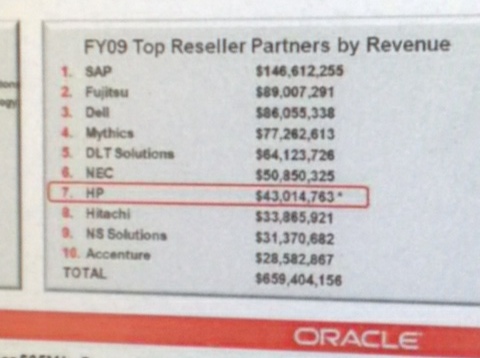

In the lawsuit filed by HP against Oracle over the support of Oracle software on HP’s Itanium-based servers, documents showed that SAP was the top Oracle reseller in 2009 accounting for nearly $150 million in Oracle database sales, as shown in the following graphic.

Salesforce.com Substitutes For SAP

At that time, SAP’s license revenues were about $3.4 billion, not much bigger than what Salesforce.com’s projected subscription revenues for fiscal 2014. That means Salesforce.com could be reselling the same amount of Oracle database, or at least $150 million annually under its nine-year deal with Oracle for a total of $1.35 billion. So from a revenue standpoint, it appears that Oracle needs Salesforce.com more than Salesforce.com needs Oracle.

By standardizing on Oracle database, Salesforce.com will benefit from reduced research and development expense and perhaps the additional leverage needed to influence Oracle’s database direction to its favor.

Mark Benioff, the CEO of Salesforce.com, understands that in return for committing itself to Oracle database, it is getting the solid agreement from Ellison that Oracle would be using Salesforce.com for sales force automation, which essentially means that it has won the CRM beauty contest. But the real test of their commitment over the next nine years is whether both sides are sticking to the new rules of engagement. If the nine-year deal stipulates that Oracle will adopt Salesforce.com in one form or another, what are the odds that Oracle will be able to leapfrog Salesforce.com in the CRM market? Similarly the deal seems to be binding Salesforce.com to the CRM market and no more. What chance is there for Salesforce.com to expand in markets like HCM as its Work.com has been endeavoring to do?

From that perspective, the strategy of Benioff, whose company has zoomed past the rest to become San Francisco’s biggest commercial tenant with nearly one million square feet of office space and 14 acres of undeveloped land in the city, reflects his desire to maintain the status quo. That stands in sharp contrast with his trademark style of disavowing anything that Oracle’s software selling stands for. One could even argue that Salesforce.com is desperate to preserve its lead in the CRM market by trading the market that it knows over those that it does not.

The question is whether Oracle will be able to use the incremental revenues from Salesforce.com to offset its potential decline in database sales in countries like China or Brazil, not to mention any erosion from the incursion into its installed base by open-source database vendors.

During the financial crisis, Oracle executives attributed its sluggish database business to the poor performance of SAP. Would it repeat the same excuse if Salesforce.com fails to extend its momentum with over 30% revenue growth every year?

Another potential issue is whether Oracle will resort to hiking database costs to such an onerous level that ends up hurting Salesforce.com, now on verge of becoming its biggest OEM partner, and its customers who already have a hard time justifying the rising costs of commodity products like databases.

During the June 27 conference call following the announcement, Ellison and Benioff were effusive in their compliments of each other in a public display of affection that reversed their long-held opposing views on everything from what constituted software to the fundamental difference between real and false Cloud. During the call, Ellison was also gracious in his comment on Amazon’s AWS, also a departure from his dismissive stance toward competing Cloud Computing offerings.

For a minute, it was as if a prima donna cranking up her charm offensive in order to be liked for the first time in a long time.

Footnote

Data for this report are based on our continuous enterprise applications market sizing research by a global team of analysts and researchers, with help from publicly available documents such as 10Ks and 10Qs along with financial results from publicly-traded parents, subsidiaries and divisions of technology companies, as well as insights from reseller partners, customers and vendor sources. See our research methodology by following this link: