The $520 million purchase of Cegedim’s CRM business by IMS Health in June 2014 offered a cautionary tale on how on-premise applications sales have been undermined by growing Cloud adoptions.

What’s remarkable about the deal was not that Cegedim has finally called it quits after years of sluggish growth, but the sharp decline in the value of its CRM business over the past few years. In 2007 Cegedim bought the CRM business from Dendrite for $751 million, meaning that the sale has resulted in a loss of at least $231 million, or 31% of its value over the past seven years.

The tale started in 1986 when Cegedim’s CRM business, formerly known as Dendrite, became the forebear of today’s customer relationship management applications market by providing electronic territory management applications for managing complex selling environments. In other words, Dendrite, which was sold to its French rival Cegedim to form a company with more than $1 billion in revenues in 2007, was selling sales force automation applications to life sciences companies and other customers seven years before Siebel, now a part of Oracle, came on the scene in 1993.

When Oracle sought to dominate the CRM applications market by acquiring archrival Siebel for nearly $5.8 billion in 2005, Dendrite and Siebel were two of the largest sales force automation applications vendors for life sciences companies. After Dendrite was folded into Cegedim, the French company would like to point out that it had bigger market share in SFA than Siebel in life sciences.

Around this time, two startups began to flex their muscle in the Cloud. First in 1999 Salesforce.com was founded making bigger waves with its Cloud-based CRM applications that its on-premise counterparts like Siebel failed to do. By the time Salesforce.com ended its fiscal 2005, it had already picked up 13,900 customers, or at least 10,000 more than what Siebel was able to secure before it was acquired by Oracle.

Still, both Dendrite and Siebel were good at selling into verticals by keeping an army of drug salespeople on a tight leash and tethering them to their laptops as they made presentations and sales pitches in doctor offices around the world. Despite its early success, Salesforce.com was not prepared to tackle Siebel and Dendrite directly in key verticals. Instead, it began to build an ecosystem of ISV partners that helped it expand by incorporating their industry-specific domain expertise like life sciences into their joint SFA solutions.

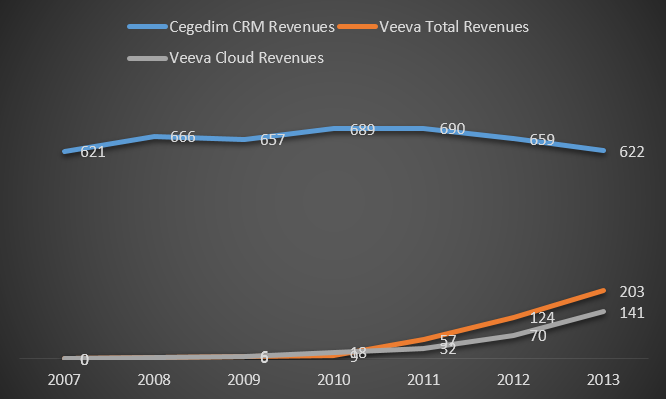

In came Veeva, which was incorporated in 2007 by leveraging the Salesforce.com platform to start selling Cloud-based CRM applications to life sciences companies, the exact target of Dendrite. During the next seven years, Veeva’s Cloud subscription revenues zoomed from zero to $147 million in its fiscal 2014 ended January 31. In October 2013 Veeva went public raising about $217 million with a company valuation of $2.4 billion. Despite the stock volatility with Cloud applications vendors in recent months, Veeva’s market cap hovered around $3 billion in mid-July.

Cegedim, on the other hand, saw its CRM business peaking at about $690 million in 2011 before slipping to about $622 million in 2013. In 2010 Cegedim Dendrite acquired healthcare data provider SK&A Information Services to shore up its CRM business. Because of the large amounts of on-premise systems that Dendrite has built and customized for its clients, Cegedim struggled to articulate its Cloud strategy.

Five months before the sale of Dendrite to IMS Health, Cegedim acquired Kadrige, a Cloud-based application vendor that focuses on e-detailing and collaborative solutions. Now both Kadrige and the CRM business with a total headcount of about 4,500 employees are expected to become part of IMS Health, a 60-year-old company better known for its massive healthcare data repository.

Meanwhile, Cegedim retreats to its remaining healthcare and insurance divisions ending its fight with Siebel and other Cloud CRM applications vendors.

Make no mistake about it, Cegedim wasn’t ignoring the Cloud at all judging from its last-ditch effort to shore up its CRM business with the purchase of Kadrige. Until legacy vendors make an all-in-or-nothing moves into the Cloud, their reluctance to cannibalize their existing recurring revenue streams could come back to haunt them.

Perhaps, Cegedim was an extreme case of an on-premise application vendor incapable of making a full-throttle commitment to the Cloud.

Cloud Push By Applied Systems, Kronos, NCR

Recent developments help illustrate how other on-premise applications vendors are breathing new life into their business by diving headlong into the Cloud, resulting in handsome profit along the way.

Both Applied Systems in the insurance software space and Kronos in the workforce management applications market have decades of experience selling on-premise products.

In 1998 when Applied Systems, which specializes in agency management applications, filed for an IPO in 1998, it had about $88 million in revenues from 7,500 brokers. At that time, all it was selling was client-server-based systems based on the Microsoft platform. It soon withdrew the IPO, weathered the Dot Com bust and finally decided to go private in 2004 with Vista Equity Partners as its new owner. Customer count went from 10,000 to about 11,000 in 2006 when it was sold to Bain Capital for $675 million. In December 2013 Hellman & Friedman paid $1.8 billion for Applied Systems, essentially more than doubling Bain’s investment.

With a current installed base of about 12,000 customers, Applied Systems has made Cloud delivery a major part of its agency management applications such as TAM, Epic and Doris. While the lofty sale price that Applied Systems was able to fetch might not be completely attributable to its Cloud push, it certainly was one of the factors.

A more striking example of leveraging Cloud delivery to boost one’s value was the February 2014 sale of a $750 million stake by Kronos to Blackstone and GIC. The deal valued Kronos, a 44-year-old vendor that pioneered the time clock applications market for workforce scheduling and time and attendance, at a whopping $4.5 billion. Kronos was taken private in 2007 when PE firm Hellman & Friedman bought the vendor for $1.8 billion.

Since 2007 Kronos’ revenues, with most still coming from its on-premise HCM applications, have jumped 56% to nearly $1 billion, while its EBITA has been growing steadily through the years. What’s noteworthy is Kronos’ uncanny ability to shed its legacy past by embracing the Cloud front and center.

Since its March 2012 acquisition of SaaShr for Cloud-based workforce management applications, Kronos has seen a sharp jump in the number of its Cloud customers signing up thousands of new ones through an aggressive push into OEM and white-label sales. In October 2012, about 6,000 customers were in the Kronos Cloud. A year later, the figure jumped to 9,000 and the current count exceeded 11,000. Despite the fact that Cloud subscription sales at Kronos still account for a minority part of its business, the relentless promotion of Kronos Cloud has helped cement its reputation as a major Cloud contender.

Then there is NCR, a venerable company that has been selling cash registers and technology products since 1884. In January 2014 it acquired Digital Insight for its Cloud-based online banking applications for $1.65 billion.

The deal, which was one of the largest purchases by NCR in recent years, came five months after Digital Insight was sold by Intuit to Thoma Bravo for $1.025 billion. In other words, NCR was willing to pay a premium of 61% for a Cloud property that it could have gotten for slightly above $1 billion just a few months earlier. The reasons cited by NCR were the need to capitalize on transformative financial services and the desire to reinvent the company.

The bold move by NCR, which has been aiming to transform itself from a ATM machine provider to a software-driven vendor with recent purchases of Radiant and Retalix for retail applications and now Digital Insight, encapsulates the quandary facing many on-premise vendors these days.

For many legacy vendors struggling to adapt to the Cloud, the answer is simple because their chances of success boil down to one thing – are they all in or nothing.